Quick starters:

- Heavy work: wall push-offs ×10, chair push-backs ×5, carry 3 books to a shelf.

- Quiet focus: watch a glitter bottle fall twice; marble-in-mesh fidget; soft putty squeeze ×20.

- Rhythm & breath: tap 8 slow beats together; “smell the flower, blow the candle” ×5.

- Transition cue: picture card (🖐 break) → routine card (Squeeze → Breathe → Decide).

What is a sensory break—and what makes it different from “playtime”?

Direct answer: A sensory break is a brief, scheduled regulation tool, not free play. It delivers specific input (proprioceptive pressure, vestibular movement, tactile/visual rhythm) that helps the nervous system reset from under- or over-arousal. Each break has a clear start, one to two activities, and a predictable end cue.

- Goal: return to “calm-alert” so attention and learning rebound.

- Structure: same place (corner, hallway, calm kit), same order (Squeeze → Breathe → Back to work).

- Length: usually 2–5 minutes; longer can backfire by stealing focus from the main task.

Sources (section): AAP—sensory integration therapies (family summary) healthychildren.org; AOTA—sensory processing practice perspectives aota.org.

Why do sensory breaks help learning, attention, and behavior?

Direct answer: Brains learn best in a calm-alert state. When arousal spikes (too loud, too bright) or dips (under-responsive, sleepy), kids lose working memory, inhibition, and flexibility. Correctly matched sensory input—especially proprioception (“heavy work”) and rhythm—can settle the stress response and restore executive function. Schools that add brief movement/sensory breaks often report more on-task behavior and smoother transitions without cutting academic time.

Put simply: short, purposeful input now → better focus later. That’s why teachers pair a 2-minute wall-push routine before writing, or parents use “glitter fall ×2 then story” as a reset after noisy errands.

Sources (section): Harvard Center on the Developing Child—executive function & self-regulation developingchild.harvard.edu; CDC—classroom physical activity resources (movement breaks) cdc.gov.

What does a great sensory break look like (step by step)?

Direct answer: Decide the lane (pressure, rhythm, quiet focus), choose one activity per lane, and stick to the same order every time. Keep language minimal; let the routine and pictures lead.

Sample 3-minute routine (class or home)

- Squeeze (40–60s): wall push-offs ×10 → chair push-backs ×5 (slow).

- Breathe (60–90s): watch a glitter bottle fall once while you model slow nasal breaths.

- Decide (20–30s): picture card: “desk or quiet corner?” → child points → return.

Teaching tip: Practice twice daily during calm times for a week. When stress hits, use the exact same sequence—your child’s body will remember.

Sources (section): AFIRM (UNC)—visual supports, prompting, reinforcement afirm.fpg.unc.edu; HealthyChildren—calming strategies for families healthychildren.org.

Home setups: small footprint, big effect

Direct answer: Create a “calm corner” with a small rug, a basket, and a routine card. Limit to 2–3 items so the choice itself isn’t overwhelming.

- Basket ideas: soft putty, marble-mesh fidget, small weighted plush (supervised), liquid motion timer, picture breath card.

- Rules: breaks are short, tools stay in the corner, one tool at a time, reset before leaving.

- Rhythm: add a hand drum or simple metronome app at ~60–80 bpm (no headphones for littles); 8 taps together, then done.

For siblings, color-code pouches to avoid sharing worries. Post a tiny schedule: “Snack → Calm Corner → Books.” Predictability is regulating.

Sources (section): AAP—toy safety/choking guidance healthychildren.org; CPSC—toy safety center cpsc.gov.

Classroom setups: efficient, predictable, and teachable

Direct answer: Build a routine, not a spectacle. Agree on a discreet signal (card, hand sign), a location (hallway spot, corner mat), and a short menu (two options only). Pre-teach the routine to the whole class so it’s normalized, then individualize as needed (IEP/504).

| Grade band | 2–3 minute menu | Where | Return cue |

|---|---|---|---|

| K–1 | Wall push-offs ×10; glitter fall ×1 | Doorway spot or calm corner | Timer chime + picture “desk” |

| 2–3 | Chair push-backs ×5; soft putty ×20 squeezes | Back table or hallway mark | Teacher thumbs-up after check-in |

| 4–5 | Wall angels ×6; square breathing ×4 | Designated “reset station” | Self-timer; sign back in |

Equity note: allow personal, silent fidgets for students who need them; set class norms (quiet, stays below desk, helps—not distracts).

Sources (section): CDC—classroom physical activity/brain breaks cdc.gov; IRIS Center—behavior & classroom management modules iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu.

How long and how often? (timing you can actually use)

Direct answer: For most children: 2–5 minutes, 1–3 times across long work blocks, plus a proactive break before known stressors (assemblies, writing, transitions). Toddlers often do best with 60–120 seconds. It’s better to take short, early breaks than long, late ones after a meltdown.

- Proactive: schedule a break 5–10 minutes before a tough task.

- Reactive: if you see early signs (fidgeting increases, face tightens), run the routine once.

- Stop point: if arousal is higher after two cycles, change the environment (leave the cafeteria, dim the room) rather than add more tools.

Sources (section): Harvard—EF works better with short, repeated practice developingchild.harvard.edu; AFIRM—prompting and reinforcement for routines afirm.fpg.unc.edu.

How do I know a break is working? What should I track?

Direct answer: Watch for quicker recovery, longer on-task time, fewer prompts, smoother transitions, and the child initiating the routine with a signal. Keep a one-line log for two weeks: (1) trigger, (2) tool used, (3) return-to-task time, (4) adult prompts. Review and adjust menu items based on that data.

In class, use neutral, objective measures (e.g., minutes on task before first prompt; number of redirects). Photos of the routine card help the child self-monitor; older students can check a tiny rubric (“ready / half-ready / not ready”).

Sources (section): CDC—Behavioral classroom strategies & observation cdc.gov; AMS—observation in Montessori practice amshq.org.

Examples by age (quiet, portable, and effective)

Babies (with caregiver, 30–60s)

- Side-lying gentle sways; soft visual (high-contrast card); “smell flower, blow candle” modeled slowly.

Toddlers (60–120s)

- Carry two soft books; scoop pompoms with a spoon into a bowl; watch glitter fall once; “push the wall” ×10.

Preschool (2–4m)

- Wall push-offs ×10 → putty squeeze ×20 → breath card ×6; or chair push-backs ×5 → metronome taps ×8.

Early elementary (3–5m)

- Hallway wall angels ×6 → square breathing ×4 cycles; mini chalkboard doodle with timer (visual focus).

Sources (section): HealthyChildren—calming & coping; developmental readiness healthychildren.org; NICHD—self-regulation research overview nichd.nih.gov.

Safety, ethics, and inclusion

Direct answer: Breaks are for comfort and access, not control. Obtain student input when possible; honor “no” to touch or specific tools; avoid noisy/flickering items; supervise weighted products and keep durations short, awake, and size-appropriate. In public or class, prioritize silent tools to respect others.

- Hygiene: personal fidgets/chews; daily cleaning for oral-motor tools.

- IEP/504 alignment: document the routine, location, duration, and staff roles; ensure substitutes have the plan.

- Language: identity-respecting terms (e.g., “autistic student” if preferred); breaks should be available without stigma.

Sources (section): AAP—weighted items safety guidance healthychildren.org; Autistic Self Advocacy Network—respectful language principles autisticadvocacy.org.

Related TinyLearns guides

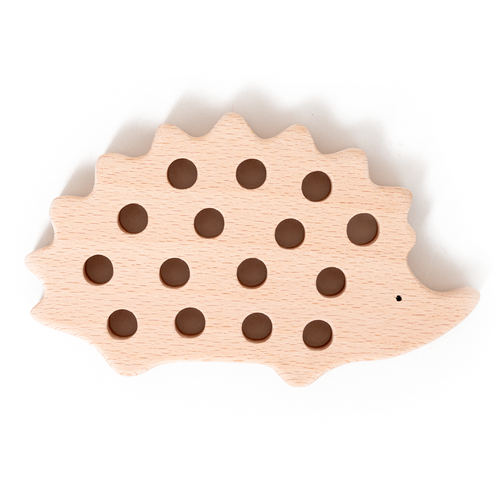

- Benefits of Sensory Play

- How Sensory Toys Help Autism & Overload Relief

- Sensory Toys by Age

- Sensory Play at Home: DIY Setups

FAQ: Sensory breaks

Won’t breaks interrupt learning?

Short, planned breaks often increase learning time by reducing off-task behavior and easing transitions. Aim for 2–5 minutes with a clear return cue.

Are movement breaks the same as sensory breaks?

Movement breaks are one type of sensory break (vestibular/proprioceptive). Many kids also benefit from quiet focus (glitter timer) or oral-motor/pressure tools.

What if my child gets more wound up after a break?

Switch lanes (from movement to pressure/quiet), lower intensity, shorten duration, or change the environment (lighting/noise). Review your data log and adjust.

Can I use timers?

Yes—visual timers are great. Avoid loud beeps; choose silent sand timers, soft chimes, or a subtle visual countdown.

Sources & further reading

- American Academy of Pediatrics — Sensory Integration Therapies: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/developmental-disabilities/Pages/Sensory-Integration-Therapies.aspx

- HealthyChildren (AAP) — Weighted Items Safety: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/chest-lung/Pages/Weighted-Blankets-and-Other-Items-What-Parents-Need-to-Know.aspx

- Harvard Center on the Developing Child — Executive Function & Self-Regulation: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/executive-function/

- CDC — Classroom Physical Activity (Brain Breaks): https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/classroom-pa.htm

- AFIRM (UNC) — Visual Supports & Evidence-Based Practices: https://afirm.fpg.unc.edu

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission — Toy Safety Center: https://www.cpsc.gov/Safety-Education/Safety-Education-Centers/Toy-Safety

- IRIS Center (Vanderbilt) — Classroom Behavior Modules: https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu

- NICHD — Self-Regulation Research Overview: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/od/odbb/self-regulation

- American Montessori Society — Observation & Prepared Environment: https://amshq.org